FRUIT TREE CARE NEWSLETTER

Bush Cherry vs Dwarf Cherry Tree: Best Picks for Your Small Garden

For generations, there was no such thing as a dwarf cherry tree. Instead, cherry trees came in one size only, and that size was "large." Cherry trees can be huge, up to three stories high. But if you have a small garden and no space for a full sized tree, what can you do?

Today, you’re spoiled for choice. You can invest in a dwarf sweet cherry tree that has been grafted onto dwarfing rootstock. Or you can opt for an easy-care sour cherry shrub. I’ll talk about both of those options in this blog.

Cherry Tree vs Bush Cherry: What's the Difference?

Historically, if you wanted to grow cherries you had two choices: a sweet cherry tree (Prunus avium) or sour cherry tree (Prunus cerasus). As their names suggest, sweet cherry trees produce lovely sweet fruit that can be eaten fresh off of the tree. Sour cherry trees also produce delicious fruit but it is not quite as sweet and often used for preserves and pies.

Until the 1990s, if you wanted to plant either a sweet or sour cherry tree, you needed to have a large garden. That’s because both Prunus avium and Prunus cerasus traditionally would grow to be more than 30 feet (9 m) tall at maturity. At that size they can shade out your yard. Harvesting and caring for such a large tree can also be quite tricky.

In the 1980s and 1990s, other options emerged with horticulturalists introducing dwarf cherry tree varieties. The secret has been in grafting. This process involves attaching the upper part of one plant (the scion) to the root system of another plant (the rootstock) to control the overall size of the tree. Researchers developed specific dwarfing cherry rootstocks, such as Gisela® 5 or Gisela® 6 so that growers can enjoy cherry trees that remain relatively small, making them suitable for smaller spaces.

Then, in 1999 things got even better for those who want to grow cherries in a small space. That’s when researchers at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada introduced their new bush cherry (Prunus cerasus x Prunus fruiticosa). Their "Romance" series of cherry shrubs are a cross between a sour cherry tree and a Mongolian cherry. The cultivars have charming names like Romeo, Juliet, Carmine Jewel. And all the options produce sour cherry fruit that rivals the size and taste of tree-grown sour cherries.

Unlike the dwarf varieties achieved through grafting, bush cherries have been bred to naturally grow on their own roots. They become multi-stemmed shrubs of a manageable size without the need for grafting. And most of the varieties that they have introduced are compact, cold hardy and self pollinating which means that you will enjoy a harvest if you only have one plant. In contrast, many sweet cherry trees are cross pollinating, which means they need to be planted near a compatible cherry tree of a different variety in order to produce a harvest.

You can compare dwarf sweet cherry trees, dwarf sour cherry trees and University of Saskatchewan bush cherries with the following quick reference chart:

| Bush Cherry | Dwarf Sour Cherry Tree | Dwarf Sweet Cherry Tree | |

| Species | Prunus cerasus x Prunus fruiticosa | Prunus cerasus | Prunus avium |

| Form | Multi-stemmed | Single trunk | Single trunk |

| Grafted | No | Yes | Yes |

| Size | 4- 10 feet, depending on variety | 6+ feet, depending on rootstock | 8+ feet, depending on rootstock |

| Canadian Hardiness Zone | 2+ depending on variety Check for US Hardiness Zone. | 3+ depending on variety Check for US Hardiness Zone. | 5+ depending on variety Check for US Hardiness Zone. |

| Self- Pollinating | Yes | Yes | Depends on variety |

| Fruit Taste | Sweet and sour | Sweet and sour | Sweet |

| Fruit Size | Average | Average | Average |

Now let's take a closer look at why you might opt for each of these cherry choices.

When Would I Opt For a Bush Cherry?

If you live in a very cold climate (colder than Canadian Zone 3), a bush cherry may be your only cherry option. Depending on the variety, these bushes are only 4- 10 feet tall and all are self-pollinating so there's no need to plant more than one- unless you want to!

But even in places with less frigid temperatures, there are reasons you might prefer a bush cherry.

Bush Cherry Benefits

- Extremely cold hardy: These cherries have been bred to survive Saskatchewan winters–that means most of them are Canadian zone 2 while dwarf sour cherry trees can be hardy to Canadian zone 3 and dwarf sweet cherry trees are only hardy to Canadian zone 5

- More likely to survive disease: Although the jury's still out on whether bush cherries have better disease resistance, their multi-stemmed structure makes it easy to prune out infected stems. But disease in a dwarf cherry tree can quickly spread to its trunk (because of its small size), possibly killing the entire tree

- Easier to prune to desired shape: To keep it healthy, a bush cherry only needs older branches removed at the base while a dwarf cherry tree requires more thoughtful and regular pruning to ensure an open, fruit-bearing structure.

Types of Bush Cherries

The University of Saskatchewan's bush cherry cultivars differ in terms of flavor and form. Here are some of the options:

- Carmine Jewel: Small pit, good for processing and fresh eating, earlier harvest, low suckering

- Valentine: Very productive, slight suckering

- Crimson Passion: High sugar content, excellent for fresh eating, low suckering, small bush

- Juliette: Very sweet, good fresh eating type, large fruit, low suckering

- Romeo: Good for juice, fresh eating, processing

- Cupid: Later harvest, large fruit, good flavor for fresh eating

- D'Artagnan: Suckers freely, makes a great fruiting hedge

- Cutie Pie: Smallest (4 feet), sweetest.

- Sweet Thing: Sweet and firm, less cold hardy.

Do Bush Cherries Taste Good?

The University of Saskatchewan bush cherries are called sour cherries, but don't let that fool you! Even though sour cherries have more acid than sweet cherries, these particular bush cherries actually contain almost the same amount of sugar as sweet cherries. This gives these fresh bush cherries a sour and sweet taste that some people love (like sour candy).

Plus, sour cherries add the delicious complexity of flavor to most cooked cherry products including pies, jams, juices and dried cherries.

To ensure the best flavor, make sure you wait to harvest University of Saskatchewan bush cherries until they're somewhat translucent and tender- they tend to turn red before they're actually ripe.

Now, bush cherries aren't for everyone. And if you specifically want to grow sweet cherries, you'll need to opt for a dwarf cherry tree. More about them next.

Types of Dwarf Cherry Trees

If you want a dwarf sweet or sour cherry tree, there are loads of choices that you will find for sale at your local fruit tree nursery but some of the more popular varieties are:

- Stella, Lapins, Black Gold: sweet and self-pollinating

- Bing, Rainier: sweet and needs another variety planted close by in order to produce fruit

- Montmorency, Evans, Surefire: sour

When choosing a grafted dwarf cherry tree, your fruit tree nursery may offer a number of rootstock options, including:

- Gisela 3: for sweet and sour cherry trees, 30- 40% of variety’s standard size

- Gisela 5: for sweet and sour cherry trees, about 50% of variety’s standard size

- Krymsk 5: for sweet and sour cherry trees, 80- 90% of variety’s standard size

- Mahaleb: for sour cherry trees, about 90% of variety’s standard size

Other Cherry Trees for Small Spaces

Although their fruit is smaller and more tart, the following bush cherries are worth a mention, as they tolerate poorer site conditions and require less care:

- Mongolian Cherry (Prunus fruticosa): 3-6 feet tall, bush, hardy to zone 2, used in jams, jellies and pies, native to Asia and Europe

- Nanking Cherry (Prunus tomentosa): 6-10 feet tall, bush, zone 2- 7, drought tolerant, some people enjoy eating the fresh fruit, used in jams, jellies and pies, native to Asia

- Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana): 20-30 feet tall, bush or small tree, zone 2- 7, drought tolerant, fruit too astringent for fresh eating, used in jams, jellies and pies, native to North America

Where Can I Buy Bush Cherries and Dwarf Cherry Trees?

There are many places that sell potted cherry trees including big box stores and garden centers. But specialist fruit tree nurseries will give you a wider selection to choose and they will send you a bare root tree that will grow faster and adapt better to your garden. My fruit tree nursery resource list can help you find a nursery that has exactly the cherry you want to grow.

Growing Healthy Cherries

Like most fruit bearing plants, both dwarf cherry trees and bush cherries are healthiest and most productive in well-drained, fertile soil with full sun, regular watering and pruning. You can learn more about growing fruit trees in my online course, Certificate in Fruit Tree Care.

But growing healthy cherries actually starts before the plants are even purchased. After learning about the different types of cherries, it's essential to choose a cutivar that will thrive in your climate as well as your unique garden conditions. This topic is covered in my online course, Researching Fruit Trees for Organic Growing Success.

So, should you choose a bush cherry or a dwarf cherry tree? Ultimately, it's up to you... just remember to consider your climate, site and taste buds!

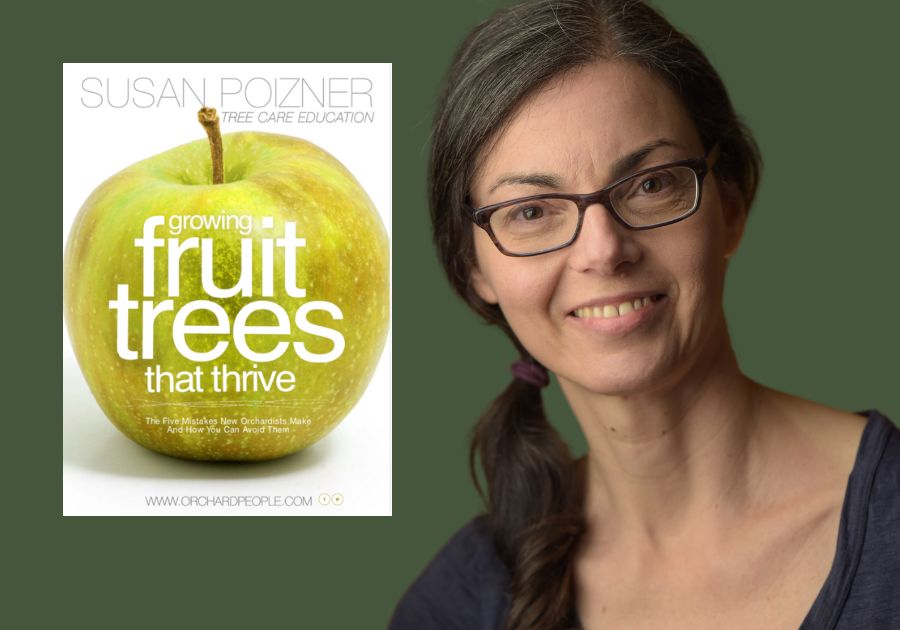

Susan Poizner

Susan Poizner is an urban orchardist in Toronto, Canada and the author of three books on fruit tree care including Grow Fruit Trees Fast, Growing Urban Orchards, and Fruit Tree Grafting for Everyone. Susan trains new growers worldwide through her award-winning fruit tree care training program at Orchardpeople.com. Susan is also the host of the Orchard People radio show and podcast and is an ISA Certified Arborist.